Kimberly Springer

Kimberly Springer

“Establishing a Black Feminist Digital Archive”

This summer’s Barnard Digital Humanities Fellowship affords the opportunity to design and build the architecture for a digital black feminist archive that will be accessible to the public. Working through questions of community archives, shared authority and digital representation, the focus is on determining the most ethical way to present materials gathered for the book, Living for the Revolution: Black Feminist Organizations, 1968-1980 (Duke University Press). Springer will be contacting narrators who participated in oral history interviews related to their time as activists with Black Women Organized for Action (BWOA), a Bay Area-based political action organizations. BOWA’s founder Aileen Hernandez (1926 – 2017) was one of the first presidents of the National Organization for Women (1970 – 1971) and spent the rest of her life developing Black women’s political leadership on the local and national levels. The documents, oral history interviews and transcripts in Springer’s possession are likely the sole archival materials related to BWOA. Deliverables include the foundations for the website on a suitable digital humanities platform, securing new releases from narrators that take into account publication on the web and improving the BWOA Wikipedia entry which is both scant and contains factual errors.

Kimberly Springer is the Curator for Oral History at Columbia University Libraries and Adjunct Associate Professor for Barnard College Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies.

Summer Fellows Blog 7/8

Despite having barely scraped by in both high school and college French, two of my favorite sayings from that language are: je ne regrette rien. “I regret nothing” is more aspirational than reality, but it resonates with me at this stage in the digital humanities fellowship and stewarding black feminist organizations’ archival materials from analog to the digital space.

I wish I could be as sanguine as Edith Piaf in her declaration that she regrets nothing when it come to reviewing this archive of black feminist organization documents. As users browse the contents of the Black Feminist Archive Online (or is it the Black Feminist Digital Archive?), you’ll note highlighting on documents.

You’ll also see pink dots stuck onto certain documents. This is a remnant of some daft idea I had around 2011 when I took a first pass at organizing these materials. What do the dots mean? Did I, in fact, include the information I recklessly highlighted when the goal was use and not preservation of these records? No idea and…probably.

All I know now, now that I have archival and preservation science principles pricking my conscience, is that I deeply, (DEEPLY) regret every highlight and dot that make these documents less than the pristine records they were when Aileen Hernandez sent them to me for my research. But these marks are also visible and useful reminders that historians and archivists are not objective or unbiased. They are, in fact, editors of histories who select, sometimes put into order, highlight and otherwise curate history.

Summer Fellows Blog 6/17

Can’t a document live? Developing an Online Black Feminist Digital Archive

Social movement researchers and social historians have come to realize that to tell the story of recent histories previously left out of the historical record, we need but ask the people who were there. We ask them the basic who, what, when, where and how of what they did to create social change. But we’re also taught to inquire after their archive: “Do you have any photos, flyers, documents?” We’re encouraged to add to the historical record through interpreting their words, but also to seek material objects that can be added to an archive for future versions of our inquiring selves.

Participating in the Barnard Digital Humanities Fellowship this summer was the final nudge in my return to documentation about black feminist organizations that I collected from 1993-1998. The organizational meeting minutes, retreat notes, small publications, mission statements, COINTELPRO papers, and a host of other records helped me to write about the pioneering place of black feminist activists and the organizations they founded nationally. In Living for the Revolution: Black Feminist Orgnaizations, 1968-1980 (Duke University Press), I used the archive and interviews with black feminists to document the historical, social and political forces that spurred black women to form five organizations: Black Women Organized for Action, the Third World Women’s Alliance, the National Alliance of Black Feminists, the National Black Feminist Organizations and the Combahee River Collective.

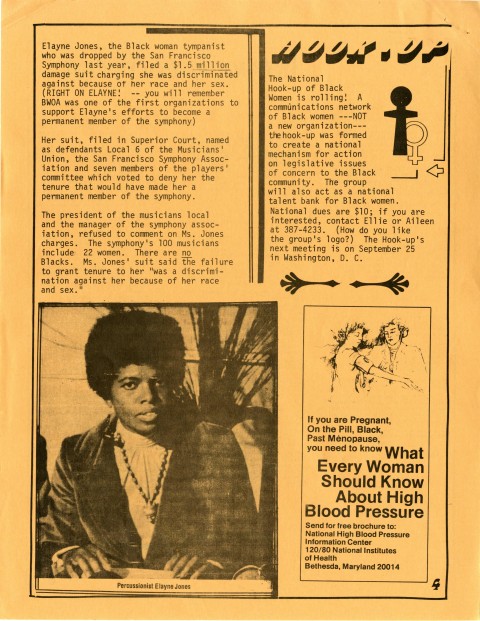

A page from BWOA’s regular newsletter detailing the group’s activities, which included connecting black women across the country engaged in political activism and defending black women in workplace disputes (BWOA, What It Is, vol. IV, no. 8, August 1976).

While I had, indeed, asked after the archives of black feminist narrators, I didn’t think about what would happen to those archives once I wrote a book that would place black feminist activism into narrative of African-American history, women’s studies and social movement history. Where should the papers of these organizations, some found unprocessed in historical societies, others culled from papers in the attics or under the beds of my interview narrators, find a home for other researchers?

It was my personal career shift from faculty to archives staff that was the major impetus for me to consider, somewhat shamefaced, where should these black feminist organizational documents continue to live so that others can make sense of the past and present and envisioning a transformative future? What I learned from moving from one side of the reference desk to the other, was about the long, problematic history of archives, but also about the practicalities of archival work. Archives are problematic in their origin and functions, but they also have the potential for repair and restoration.

A major goal of this project is to bring to the fore all of the black feminist organizations that were active in the late 1960s through 1980s. As pivotal as the Combahee River Collective was, and remains, to the formation and theorizing of black feminist theory and action, they were not the only group enacting intersectional politics before Kimberle Crenshaw and other critical race theorists developed intersectional theory and that theory made its way into the popular discourse.

This summer I’m focused on creating the foundations of a black feminist organizational archive online. I’ll be using Black Women Organized for Action’s records as the basis for the archive because, to my knowledge, these papers exist nowhere else. BWOA’s founder, Aileen Hernandez, deposited her personal papers with the Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College, but these documents aren’t widely accessible nor online.

A central idea under consideration as I develop this archive and consider the ethics of doing so is Lae’l Hughes-Watkins’ thinking on the reparative archive. What are my responsibilities as an archivist to these materials? To the historical record? How do ethics around preservation play a role in presenting this material digitally?

I have always maintained that a broader view of black feminism and black feminist activism isn’t dependent on one person and shouldn’t focus on one group, organization or collective. Crafting a responsible black feminist organizational presence online is, but a small contribution to sharing with activists and researchers ways of thinking about a black feminist future in all of its myriad political formations and configurations.